A trailblazer in preventing sudden cardiac death

Charles Antzelevitch, PhD, and his Lankenau Institute for Medical Research (LIMR) team have been partnering with the Mayo Clinic for the past four years on preventing a pair of rare deadly causes of sudden cardiac death. A breakthrough this summer shows that a traditional Chinese medicine from plants such as safflower may be an answer.

For Antzelevitch, the discovery is merely the latest of a series of advances he and his cardiovascular research team have achieved in exploring these hereditary conditions. The LIMR professor has been at the forefront of research to stop these killers for 35 years.

Antzelevitch's curiosity was first piqued by a U.S. government report on a mysterious syndrome responsible for a spate of deaths among young Southeast Asian refugees. The findings were not news in the refugees' native lands. In the Philippines, the mysterious syndrome was called bangungot (to rise and moan in sleep). In Japan, it was pokkuri (sudden unexpected death at night). In Thailand, it was Lai-Tai (died during sleep).

"It was also known as voodoo death," says Antzelevitch, executive director of LIMR's Cardiovascular Research Program. "Because it affected mainly young males primarily under 40, those in families that had experienced this would go to sleep dressed in female clothes to ward off the evil omens thought responsible. As I learned more about these deaths, the stories intrigued me. My desire to save those with this devastating syndrome is what drove me then and continues to drive me today."

Discovering and naming Brugada syndrome

Antzelevitch and colleague Gan-Xin Yan, MD, PhD, discovered an as-yet-unnamed condition while studying a type of arrhythmia (irregular heart rhythm) in experimental models. A chance encounter with a renowned French cardiologist on a bus during a conference in Florida led to a suggestion that Antzelevitch contact the Brugada brothers—Spanish arrhythmia specialists who had encountered cases with similar profiles in humans.

"We started to work together, and it became clear that what the Brugadas described in the clinic was what we saw in the laboratory," Antzelevitch says. "They published their findings in 1992, and in 1996, Gan and I published our research, naming the syndrome after them."

Unexplained fainting is one of the most common symptoms of Brugada. Once patients develop symptoms, there is a 50% chance they will die within 10 years. Some 150,000 Americans may be at risk of sudden death from Brugada.

Antzelevitch's team soon discovered that Brugada had similarities to a second condition called early repolarization syndrome. Early repolarization is a common finding in electrocardiograms. However, recent studies show that this condition, previously thought to be benign, can sometimes lead to arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. They then showed that the mechanisms involved were similar to those responsible for life-threatening arrhythmias that develop during hypothermia, or dangerously low body temperature.

Antzelevitch and his colleagues linked these cardiac conditions under a new name: J-wave syndromes.

The path to Mayo and a natural treatment

Based on their understanding of the mechanism underlying the J-wave syndromes, Antzelevitch and Yan in 1999 suggested quinidine as the first pharmacologic treatment for the J-wave syndromes. Quinidine is one of the oldest drugs used to treat abnormal heart rhythms. What they had long sought, however, was a potassium channel blocker that selectively blocks a specific electrical current in the heart believed primarily responsible for these deadly syndromes. It eluded them for over 20 years.

During a conference several years ago, however, their luck changed. A doctor from Hong Kong, Gui-Rong Li, reported that a traditional Chinese medicine called acacetin blocks three electrical currents, including the one identified by LIMR as the culprit in the life-threatening arrhythmias. At Antzelevitch's request, Li sent some acacetin, and testing at LIMR found it to be extremely effective in preventing the dangerous arrhythmias.

Acacetin has long been used in China for a range of conditions including rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, bronchitis, impotence and altitude sickness. It's also been reported to have strong anti-inflammatory and anticancer activity.

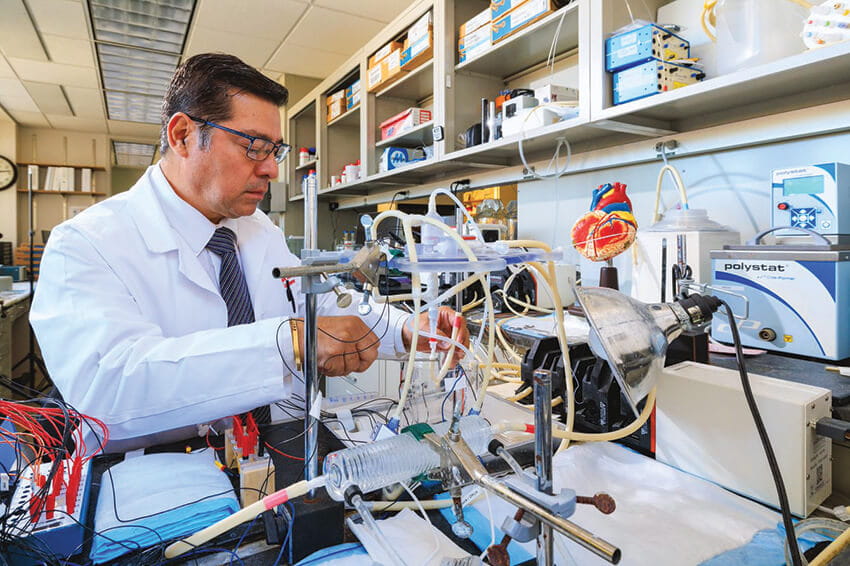

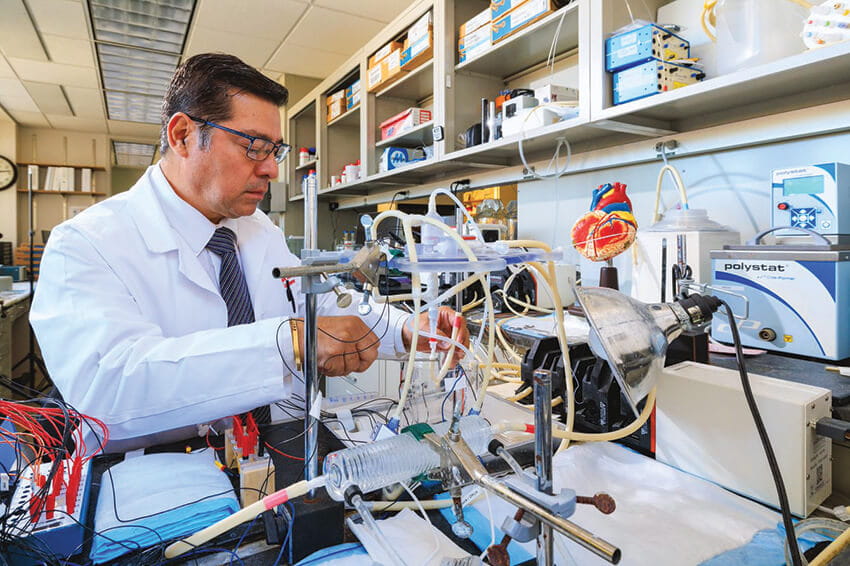

Eager to obtain clinical data on acacetin's effectiveness as an anti-arrhythmic, Antzelevitch contacted his friend Michael J. Ackerman, MD, PhD, at the Mayo Clinic and the collaboration with LIMR was launched. Ackerman's team at Mayo identified two patients with Brugada syndrome possessing mutations in the gene believed to be the culprit. LIMR research professor Héctor Barajas-Martínez, PhD, cloned the gene and showed in the lab that it increased the current they had determined was responsible for the sudden death syndromes and showed that acacetin blocked it, preventing the irregular rhythm. Also, José Di Diego, MD, developed a three-dimensional model of a heart with J-wave syndromes. The latest study was published in Circulation: Genomic and Precision Medicine in July 2022.

"We're fairly convinced this is going to be a safe drug," Antzelevitch says. "Its history of use in China for years gives us a lot of confidence."

LIMR's research with acacetin continues, but there are challenges. It has limited ability to dissolve in liquid, hampering efforts toward an FDA-approvable drug. So, LIMR is working to find a drug with similar features to acacetin but one that would be more soluble and at least as potent in blocking the current.

"We need to find a drug that will selectively block the current that is at the heart of these sudden cardiac deaths," Barajas-Martínez says.

"We still have a ways to go," Antzelevitch adds. "But I'm confident that we will ultimately arrive at an effective drug to protect patients afflicted with these syndromes. We're grateful to the individuals and federal funding agencies who made these studies possible, including Wistar and Martha Morris, who funded my early years at LIMR, as well as the W.W. Smith Charitable Trust."

The National Institutes of Health has provided $2.93 million, or 95%, of the more than $3 million in funding received to date.

Read more from Catalyst Magazine

Learn more about Lankenau Institute for Medical Research (LIMR)