Main Line Health researchers use environmental and industrial contamination data to identify local hotspots for urologic cancer

Using a blend of medical, environmental and census data, Main Line Health researchers examining the incidence of urologic cancers identified three local hotspots.

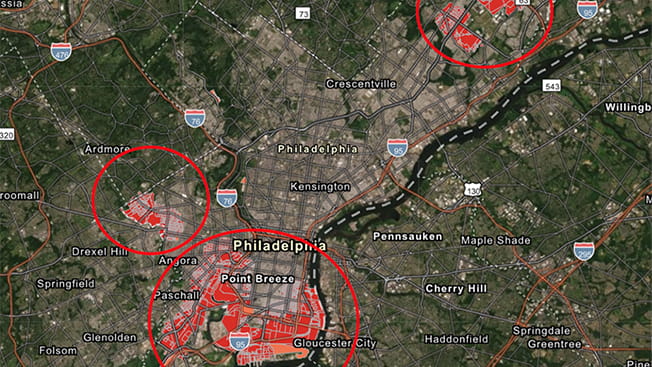

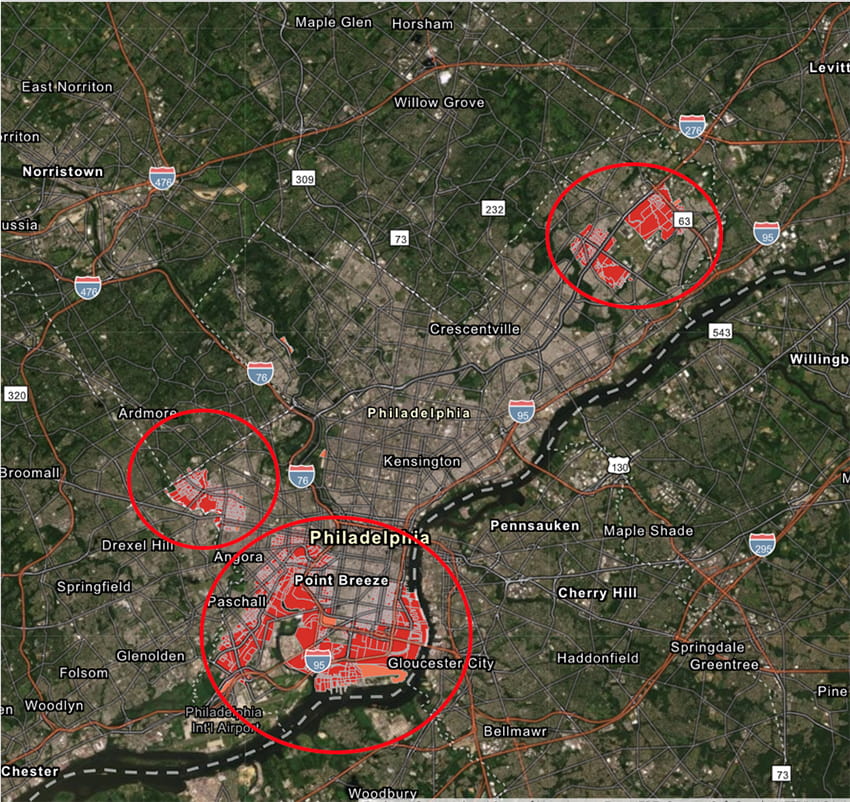

The hotspots, or areas with a significantly higher incidence than statistically expected, were in a large section spanning South and Southwest Philadelphia, portions of Northeast Philadelphia and parts of West Philadelphia. Patients residing in these hotspots lived near sources of industrial discharge of known cancer-causing substances and areas of greater traffic volume. They also were more likely to be lower income and nonwhite.

The study originated with clinicians from Main Line Health’s urology group. They collaborated with experts from the Center for Population Health Research at the Lankenau Institute for Medical Research (LIMR), part of Main Line Health, whose expertise contributed to the examination of the data across the five metropolitan Southeastern Pennsylvania counties.

Tobacco use is the most well-documented risk factor for urothelial carcinoma, which is the predominant type of bladder cancer, and is associated with up to 65% of all such cancers. However, this study also found an association between living in a urothelial carcinoma hotspot and proximity to discharge of industrial byproducts and environmental pollutants.

Crucially, the cancer patients living within these hotspots were less likely to be tobacco users but more likely to live in proximity to discharge of chemicals such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (produced in the burning of oil and gasoline). The findings point to chemicals and pollutants having a greater effect than tobacco on these industrial-area residents. Additionally, living within proximity to areas of greater traffic volume exposes these patients to products found in engine exhaust, which also contains many of these same compounds.

“We do a lot of partnering with our clinicians, and this is an example of the result,” said Sharon Larson, executive director of the Center for Population Health Research and one of the coauthors. “I’m pleased with how our team of authors dug deep, used the wealth of data resources at their disposal, and found new information that presents a totally new picture of cancer hotspots in our region. This study opens the door to further investigation of how income, race and environmental factors interplay.”

Paulette Dreher, Zachariah Taylor, Daniel Kim and Laurence Belkoff were the researchers for the Main Line Health urology group. They were joined by Meghan Buckley, Guy Bernstein, Daniel C. Edwards (now with the Center for Urologic Care of Berks County) and Larson of the Center for Population Health Research. Gabrielle R. Yankelevich of the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine was the lead author.

“This is the type of work that can have a real effect on policy,” said George Prendergast, LIMR president and CEO. “It is a great example of what Main Line Health excels at, performing high-level scientific research that policymakers can use in preventing cancer cases in the future.”

Hotspot patients were significantly more likely to be nonwhite (38% of patients living in a hotspot were nonwhite vs. 11% living elsewhere) and live within 1,000 yards of an airport, industrial discharge site or increased traffic. White patients were 94% less likely than nonwhite patients to live in a hotspot. Hotspot patients were also more likely to be lower income and less educated.

The study looked at patients ages 40 and older diagnosed with urothelial carcinoma of the bladder and other related cancers. Patient addresses were mapped to Census data, which was overlaid with Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency data on known sources of discharges of cancer-causing agents into soil, air or waterways. The researchers also looked at traffic density data from the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation due to health effects of vehicle emissions. Additionally, they included areas near Philadelphia International Airport and Northeast Philadelphia Regional Airport as potential sources of contaminants due to their high aircraft volume and the associated airplane exhaust, another potential source of carcinogens. Ultimately, although traffic density and industrial contaminants remained risk factors, proximity to airports did not remain significant on a multivariable analysis.

Of the 5,080 patients whose data was studied, 148, or 2.9%, lived within a hotspot. The data represents approximately half of all urothelial carcinoma patients diagnosed in the area over a 10-year period (2008-2018). It is possible other hotspots are unaccounted for, but the large patient sample suggests these results are likely representative. The study, “Socio-environmental conditions associated with geospatial clusters of urothelial carcinoma: a multi-institutional analysis,” appears online in the Journal of Urology and is currently in press.

Contact

Gina Mahon

Communications Manager

Office: 484.580.1026

MahonG@mlhs.org

About Lankenau Institute for Medical Research

Lankenau Institute for Medical Research (LIMR) is a nonprofit biomedical research institute located on the campus of Lankenau Medical Center and is part of Main Line Health. Founded in 1927, LIMR's mission is to improve human health and well-being. Using its ACAPRENEURIALTM organizational model that integrates academic and entrepreneurial approaches, faculty and staff are devoted to advancing innovative new strategies to address formidable medical challenges including cancer, cardiovascular disease, tissue regeneration, gastrointestinal disorders and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. LIMR's principal investigators conduct basic, preclinical and clinical research, using their findings to explore ways to improve disease detection, diagnosis, treatment and prevention. They are committed to extending the boundaries of human health through technology transfer and training of the next generation of scientists and physicians.